The most important skill to master in dragon boating is, of course, the stroke. The paddling technique is simple enough that a beginner can begin an approximation of the technique in his or her first few practices, but to move the boat with the power required in competitive racing requires a constant effort to refine the various elements of the stroke.

Most beginners will find dragon boat paddling awkward, because it places you in an unnatural position: paddling on one side only, pulling the water rather than pushing it (as in other paddle sports such as kayaking), and keeping the stroke all up in front of you. But with time, the body will become used to this positioning and it is then that true progress towards becoming a competitive dragon boat paddler will be made.

There are four phases in a dragon boat stroke: Catch phase, Power phase, Exit phase & Recovery phase. (Ref. AusDBF Level 1 Coaching Workbook 2013)

Catch phase:

This is the beginning of the stroke. It begins with the paddler out- stretched, reaching forward with the paddle out of the water. The inboard arm drives the paddle downward as the outboard arm helps push the blade deep under the water.

- The body is leaning forward over the front (outboard) leg.

- The outboard arm and shoulder is fully extended with the elbow straight.

- The waist/hips are rotated so that the outboard shoulder is forward and the inboard shoulder is back.

- The inboard arm is also reaching forward with a slight bend no higher than the top of the head.

- The blade is fully buried before it is pulled back.

- The blade catches close and parallel to the side of the boat.

- The angle of the blade on the catch is sloping forward at 45o to the water.

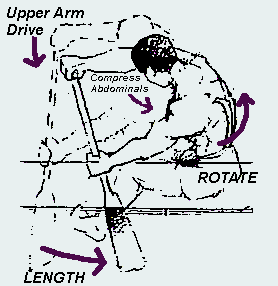

Power phase:

This is the working part of the stroke that contributes to boat speed. The inboard arm maintains downward pressure and the outboard side does most of the work in dragging the paddle backwards.

Largely, this is done with a straight arm; however the elbow does bend slightly as the phase continues. The abdominals are also tightened to form a stable trunk in order to transfer the power of the upper body.

- Power is only applied after the paddle has locked onto the water.

- The outboard leg is driven into the floor of the boat to transfer power and engage hips and abdominals in the stroke.

- The outboard arm remains almost straight as the larger muscles of the body do most of the work.

- The waist rotates as the outboard shoulder is pulled back behind the inboard shoulder.

- The inboard arm provides downward pressure to keep the paddle at a constant depth in the water.

- The outboard arm ideally makes a horizontal path along the top of the water.

- The inboard arm must not move down to the gunwale or punch forward but stays fairly high until the end of the stroke.

- The direction of the pull is along the side of the boat.

Exit phase:

This phase involves lifting the paddle out of the water. This is best done by taking the paddle out to the side and feathering the blade (rotating it to cut into the direction of travel).

The outboard elbow bends only slightly as the paddle moves across the water, by lifting the out- board elbow to the side.

The exit should be a relaxed movement.

Lifting the paddle up and close to the boat bending the outboard elbow (‘choo-choo train’ style) requires a lot more energy and introduces too much elbow action into the power phase.

The exit needs to be fast and clean to avoid dragging the blade at the end of the stroke.

The exit should not go too far back but it does need to have an effective blade exit with rotational power applied to make the boat glide during the recovery.

The paddle leaves the water cleanly and quickly midway between the paddler’s hip and knee.

Recovery phase:

This brings the paddle forward above the water, to an outstretched position with the paddle out of the water, ready to take another stroke.

- The paddle moves out and slightly to the side with the blade angled to cut into the direction of travel (feathered).

- The shoulders and back should be relaxed.

- Rotation occurs through the waist as the arms and shoulders begin to reach for the catch.

- Both arms are only slightly bent.

Each of these components of the stroke is equally important and must be done in synchronisation with the paddler across and in front. If done correctly, all paddlers will be in time with the lead strokes.

If paddlers are not synchronised, each successive pair of blades hits the water a fraction of a second behind the blades in front of them. To an onshore observer, this effect resembles the movement of a many-legged caterpillar or centipede; thus, a coach may discipline a team for “cater pillaring.” During a race, it is difficult to stay in sync as the sounds of other drums make it confusing or unreliable to time off the drumbeat.

Experienced paddlers will feel the response of the boat and its surge or resistance through the water via the blades of their paddles, and will adjust their reach, and the catch of their blade tips, in accordance with the power required to match the acceleration of the hull through the water at any given moment.